Arcadia Ireland

Ireland and Black History Month

Before February draws to a close, I wanted to share some of my thoughts about Black History Month and its significance in contemporary Ireland. In Ireland, our observance of Black History Month and our relationship to and understanding of the concept of race are very different from that of our US counterparts.

The first distinction is in the month of the year in which Black History Month is observed. In the USA – where its origins go back to an older event, “Negro History Week”, established in the 1920s by Carter G. Woodson’s Association for the Study of Negro Life and History – Black History Month takes place in February. Confusingly to those of us exposed to the American as well as the British and Irish cultural spheres, the same period of celebration and commemoration takes place on this side of the Atlantic not in February but in October.

But the time of year when it is observed is not a fundamental difference. I am much more interested in the question of how to mark such a season meaningfully in a country like Ireland. I say “in a country like Ireland” not with a sense of despair at a place where public awareness of the importance of race or racial equality are lacking. Far from it: a quick Google search reveals that Ireland is home to one of the earliest incarnations of Black History Month as “only the fourth country in the world (after the US, the UK, and The Netherlands) to officially honour Black culture and heritage in this way.” (Although its precise ranking in the chronology may be open to debate, as a little more time on Google reveals that both Canada and Germany initiated their own versions of a Black History Month in the 1990s.) The first instalment of Black History Month in Ireland was held in Cork in 2010, and the movement has only gathered momentum since then.

Ireland’s position at the international forefront of observing Black History Month is both admirable and a little puzzling. Admirable for obvious reasons, as it bespeaks the presence of an enlightened streak of humanism and compassion. A little puzzling because of Ireland’s history and the demographic profile of its population.

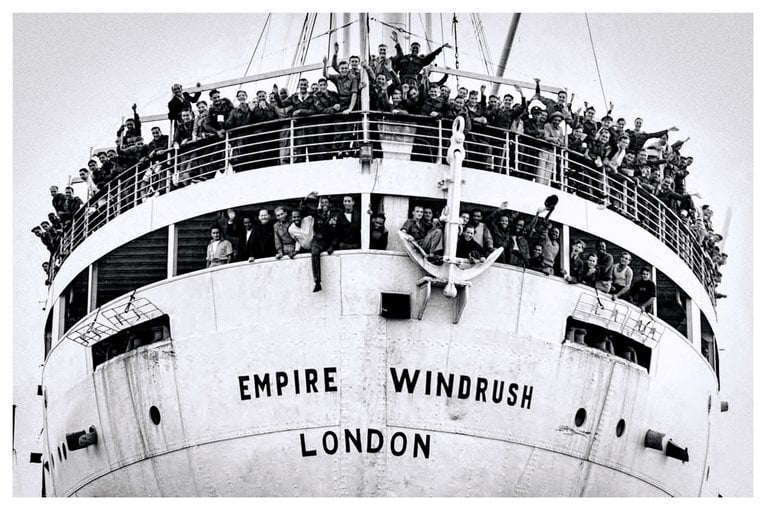

All the other countries where Black History Months were instituted before Ireland were either former colonial powers (like the UK or The Netherlands) or nations centrally implicated in the slave trade (the US). The racial make-up of the modern populations of these countries reflects that past, as a significant proportion of the population identifies as Black, African, Afro-Caribbean, African American, Black British, or whatever other box they may choose to tick on a census form. Whether they were the descendants of emancipated slaves following abolition, subjects from former colonial territories, or arrivals from the Windrush generation in the post-War era, historians in both the US and the UK needed to take stock of the contributions these non-white protagonists had made to their national histories.

Ireland is different. In the 2016 Census of the population (the preliminary results of the 2022 Census released at the time of writing do not yet include the numbers for ethnicity), more than 82% of the population identified as “White Irish”, and the next biggest group was “Any other White background” (9.5%). These percentages do not even include Irish “travelers”, who are counted as a separate category. This means that less than 7% of the population identifies as not white. The largest non-white population group is made up of those of Asian descent (2.1%), followed at some distance by those who describe themselves as “Black Irish”, “Black African” or “Other Black”. Those various “Black” ethnic groups accounted for less than 1.4% of the total population of Ireland in 2016.

In other words, the question of race traditionally has been and remains for most of us in Ireland a theoretical one in our daily lives. We simply do not see the same variety of skin colours when we venture out into the streets, the workplace or educational institutions.

So what accounts for the seemingly anomalous introduction of a Black History Month so early in our history compared to certain other, perhaps more likely countries? It has often been suggested that Cork was a particularly appropriate location for the first Irish Black History Month in 2010 because that city was the home of a large number of anti-abolition societies in the nineteenth century. It was also the city where Frederick Douglass (the escaped slave turned abolitionist campaigner mentioned previously) landed in 1845 to begin his lecture tour of Ireland.

One of the reasons that brought Douglass to Ireland was his desire to meet Daniel O’Connell. O’Connell remains best known in Ireland as the leader of the movement that agitated for Catholic Emancipation in the 1820s, but he left his mark on other, related areas of political thought far beyond these shores, both within and beyond his own lifetime. (In fact, the way in which reverberations of O’Connell’s pioneering methods for non-violent civic disobedience as an effective way of forcing policy change in an unwilling, or even hostile, political system could be felt in the twentieth century equal-rights movements of Martin Luther King’s America and Mandela’s South Africa is the subject of the epilogue of Patrick Geoghegan’s magisterial two-part biography of O’Connell.) The O’Connell of whom Frederick Douglass came in search was one of the most vocal abolitionists in Europe, an elected Member of Parliament who did not hesitate to speak out against the “foul stain” left on the United States’ national character by its continued tolerance of slavery, who retrospectively criticised the architects of US independence of a lack of “moral courage” for their failure to outlaw slavery in the Declaration of Independence, and who on one occasion was even nearly challenged to a duel by the American ambassador in London for describing him as a “slave breeder.”

Douglass did eventually meet O’Connell, on 29 September 1845, after O’Connell addressed a large crowd gathered in Dublin to hear him speak about repealing the political union that tied Ireland to Great Britain. Douglass recorded O’Connell’s words on that day in his Life of an American Slave, the memoir published in Boston later that year. “I have been assailed,” O’Connell told the crowd,

for attacking the American institution, as it is called,—Negro slavery. I am not ashamed of that attack. I do not shrink from it. I am the advocate of civil and religious liberty, all over the globe, and wherever tyranny exists, I am the foe of the tyrant; wherever oppression shows itself, I am the foe of the oppressor; wherever slavery rears its head, I am the enemy of the system, or the institution, call it by what name you will.

I am the friend of liberty in every clime, class and colour. My sympathy with distress is not confined within the narrow bounds of my own green island. No—it extends itself to every corner of the earth. My heart walks abroad, and wherever the miserable are to be succored, or the slave to be set free, there my spirit is at home, and I delight to dwell.

This acute sense of justice, this instinctive sense of empathy with the downtrodden and the disenfranchised, is the mood Douglass encountered all over Ireland during his travels in the summer of 1845. (Though some have argued that his timing was fortuitous: that Douglass’s visit took place in the last season before the start of the Great Famine (1845-48), and that the mood of the Irish population may have been less receptive to the plight of the escaped slave in the midst of deprivation and starvation.) Moreover, he recorded in a letter the “total absence of all manifestations of prejudice against me, on account of my color”, adding that “I find myself not treated as a color, but as a man.”

Douglass’s report of O’Connell’s speech and his appraisal of the Irish habit for not defining him by his colour rather neatly sum up the Irish attitude towards race. They are instinctively on the side of those downtrodden population groups who are often set apart by the colour of their skin, while not being used to seeing different skin colours around them.

This attitude goes back to Ireland’s unique position in the history of European colonialism. Many historians and cultural and literary critics have argued that Ireland is a postcolonial nation, that Ireland was Britain’s nearest and first colony, a colonial laboratory in which they tried out many of the policies they would later implement in Africa, Asia and the Americas, and that they treated the native Irish as inhumanely as they treated the natives of all their other colonies. This argument has many merits. From the earliest settlements onwards, there was a concerted effort to paint the Irish as “other” – as strange and foreign and exotic, and therefore as threatening and hostile and, ultimately, as less developed or even subhuman. Think of all the Punch cartoons of the nineteenth century that made the Irish appear as simian and predatory. This kind of smear campaign was necessary to justify the way the Irish were treated. And at the root of making that kind of thinking possible was the premise that the Irish were not just culturally or linguistically or religiously, but ethnically distinct from the British. Even the more benign Romantic theories (by late-nineteenth-century intellectuals like Matthew Arnold or even W.B. Yeats) about the innate mystical or poetical character traits that distinguished the Celts from Anglo-Saxons are premised on the underlying assumption of a racial or ethnic otherness between these distinct groups of white-skinned Europeans.

There is a different school of thought, however, which argues that to classify the Irish experience of British rule as colonialism, on a par with the colonial experience of Africans and Asians in other former British territories, is not quite accurate. The central part of this counter-argument is that of race: the Irish could never experience the same level of “otherness” within the empire simply because they did not fundamentally look different from their colonial masters. They were both white, and so there was no fundamental distinction of ethnicity. If an Irishman decided to turn coats and make himself British, all he needed to do was to learn the language and adopt the correct accent, to dress for the part and give himself a properly English sounding name. There are countless examples of this both in literature and in historical reality. Oscar Wilde became more English than the English themselves (so much so that some foreign visitors to Dublin are shocked to learn that he was Irish in the first place), and the low-born Irish-speaking Owen in Brian Friel’s great play Translations (1980) is happy to enlist as a civilian translator with the Royal Engineers and be re-Christened Roland (a name originating in the Romance languages of his Anglo-Norman paymasters). In the United States, millions of Irish immigrants arrived to make new lives for themselves since the time of the Famine, and many of them managed to escape the stigma of the drunken disorderly Irish by occluding their Irish origins. They could do so relatively easily by softening their accents and perhaps changing their names in the same way open to immigrants from other European countries. (In that great American novel of the early twentieth century, the hero dazzles the world by turning himself from poor unremarkable Jimmy Gatz into the aristocratic sounding Jay Gatsby.) They could do so because they were white. A black man was free to change his voice and his name in the same way, but he would still stand out as different.

This is where the Irish experience is so distinctive. The Irish know what it means to be colonised, to be suppressed and “othered” in one’s own country by an invading foreign power. They share this historical experience of colonialism with many other peoples around the globe. But the Irish experience is different from that of most other postcolonial nations because of its geographical location, as since it is located so far north of the equator the lines drawn between coloniser and colonised are not delineated along lines of race.

As a result, the Irish have often been seen (by outside observers like Frederick Douglass) or even thought of themselves as possessed of an innate empathy and understanding for the experience of oppressed ethnic groups. In the case of the migrant experience of those who escaped the Great Famine to the United States in the nineteenth century, or indeed members of a later generation who left Ireland as economic migrants after independence in the 1940s and 1950s, it is true that the Irish were often classed together with those ethnic groups as an undesirable underclass. Both in the UK and the US, the Irish often ended up working the kind of tough physical jobs that had been reserved for black slaves before abolition, and most people in Ireland even today are familiar with stories about the notorious signs on the doors of English pubs and boarding houses that proclaimed “No Blacks, No Dogs, No Irish.”

But it would be facile to suggest that to be Irish is the same as being black, or that to be Irish means understanding exactly – or even partially – what it feels like to be black, to be marginalised or even persecuted because of the colour of one’s skin. There may have been a natural affinity between the colonised Irish neglected by the politicians in Westminster (and soon left to starve after repeated failed potato harvests) whom Frederick Douglass encountered on his travels in 1845, and even a shared experience of ostracization at the hands of a white middle-class British establishment that threw Irish immigrants together with the new arrivals from Asia and the West Indies in post-War Britain; but as Ireland has become increasingly modernised in recent decades and economic migrants started coming into Ireland instead of leaving it for the first time in the 1990s that understanding is becoming an increasingly distant memory very quickly.

Not that we have forgotten about the need for empathy – for placing ourselves imaginatively in the shoes of a member of a marginalised race. One of the most poignant reminders of the enduring capacity for that leap of imaginative sympathy in the literature of post-Celtic Tiger Ireland came in that most unlikely of Irish novels, written by that most unlikely of Irish authors. Written by an author who was born in Cork of an Irish father and a Turkish mother, Joseph O’Neill’s Netherland (2008) follows a white Dutch investment banker as he gets immersed in the cricket scene in New York. Of the many things that anchor the book in an Irish literary and intellectual tradition, one is its affinity with the emigrant experience, and specifically with the awareness of one’s own whiteness amid the dark faces of those who share many of the other facets of that experience. The protagonist soon becomes aware that the sport he spends his time playing is an immigrant sport in his adoptive city, and that as such both the players and the game are treated as second-class by the general population. As a member of the privileged white upper-middle class, this experience of marginalisation is new to him – which leads him, in a not-isolated moment of introspection and aphorism, to coin the idea that sometimes is it necessary to “put on white [referring to the white clothing worn by cricketers] to feel black.”

That novel’s protagonist’s recognition of the sense of “otherness” experienced by dark-skinned cricket-playing immigrants is important – but so is the knowledge that his understanding is only limited. A white man may don cricket whites in the USA and “feel black”, but he should know that any insight he may gain into the daily reality of those with a different skin colour – the team mates from Sri Lanka, Barbados and South Africa – is only superficial and temporary. As a white man, he can only understand the experience theoretically; he can never fully share it.

*

All of this brings me back to the question of writing something meaningful to mark Black History Month in Ireland.

Given the comparatively long-standing history of the event in Ireland, I felt it was appropriate to mark it in some way in this space. The problem was that there is very little material to draw on for such a piece, given that Ireland remains such a predominantly white nation. I couldn’t really write a piece about a significant black Irish political figure, for the simple reason that there isn’t anyone to fit that bill. The nearest thing would be a piece about Barak Obama (whose Irish ancestry in County Offaly had been widely reported upon during the then-President’s visit to Ireland in 2011), or about Frederick Douglass. But Douglass was not Irish – nor were some of the other iconic black figures whom I vaguely knew had visited Ireland at some point in their careers. (A black-and-white photograph of Muhammad Ali brandishing a hurl during a visit to Croke Park in 1973 that I had seen framed on the wall of a pub in the West of Ireland just a few weeks ago came to mind.)

Nor did I want to write a facile piece about one of our few-and-far-between black Irish celebrities, past or present. I did toy with that idea, and even re-read a biography of Phil Lynott – the illegitimate son of a white Catholic Irish mother and a black British Guianese father who grew up to become Ireland’s first proper rock star. The young Lynott started life as the only black boy in the working-class Dublin suburb of Crumlin, and the image of the seven-year-old black boy standing in the playground on his first day in school while all his classmates excitedly crowd around to touch his curly black hair, or the anxious question asked by the mother of one of his classmates when her son’s black friend visits their house for the first time (“Does he drink tea?”), are in a very real way indicative of the innocence – an attitude by no means malicious or prejudicial but certainly not acceptable to our twenty-first-century norms of behaviour – with which the Irish typically approached race in those days.

In the end, however, I decided that the most useful piece to come out of Ireland during this month of the year would possibly be one that took stock of the very existence of Black History Month in Ireland, on the relative scarcity of black experiences in Ireland and on the familiar trope of the Irish affinity with the oppressed and the marginalised, while also acknowledging the limitations of that kind of understanding.

If Black History Month celebrations are always going to be on a relatively modest scale here in Ireland, then this is because as a nation we do not carry the same historical baggage surrounding issues like colonisation and slavery as many other Western countries. Perhaps the most important function that an initiative like Black History Month can fulfil in a predominantly white country with a monochrome history like Ireland is to remind us all of the existence of black histories around the globe – and of the way in which the histories of the black populations of the world are tied up with our own histories.

It has been said that we should study history so that we may not be condemned to repeat it. As a comparatively mono-racial culture – notwithstanding the perceived differences between white Celts and caucasian Anglo-Saxons – Ireland may not have a history of fraught race relations to learn from as we head into the future. (Remember James Joyce’s wry joke in Ulysses, where he has the jingoistic Mr Deasy gloat to Stephen Dedalus that Ireland is the only nation never to have persecuted the Jews … for the simple reason that she never let them in in the first place.) But in our increasingly globalised reality, where the Irish find themselves mixing with members of other races and taking part in global conversations about equality and race, we should welcome any opportunity to study the global histories of race relations. This is why Black History Month – in whichever month of the year it is marked – matters in a country like Ireland as well as one like the United States.