Arcadia Ireland

Cuchulainn and the Cricketers: Sporting Codes

Something momentous took place during last week’s Orientations programme for our Arcadia summer students in Dublin – something I did not ever expect to see, let alone participate in.

For some time now, one of the highlights of Arcadia Ireland’s orientation programme for newly arrived students each term has been an afternoon playing Gaelic games. Until recently, this has always taken place at the grounds of Na Fianna GAA club in Glasnevin, a suburb in north Dublin, where our partners of Experience Gaelic Games have their base. Cormac and Georgina and their team of enthusiastic young coaches have always looked after us really well at their club home, and Arcadia students have always had a blast being taught to play hurling and Gaelic football.

Last week, however, things were a bit different. No longer did we make the journey to Glasnevin to don our protective helmets on the suburban astroturf pitches of Na Fianna, overlooked by the back windows of redbrick terraced houses – a set-up that feels connected to the local community by this very geography. Instead, we met Georgina in the heart of the historic city centre of Dublin, on the cricket pitch of Trinity College Dublin – the pitch where Samuel Beckett played when he was a student at that venerable institution.

This may not seem remarkable to outsiders not familiar with the lines of class, religion and political allegiance that have historically divided Irish society – and I doubt it was remarkable to many of our students on the day. Most Irish people, however, would be acutely aware of how the playing of Gaelic games on the cricket pitch of Trinity College signals a profound cultural shift that has taken place in Irish society since the days when Samuel Beckett donned his traditional cricket whites here almost exactly a hundred years ago.

To understand why this is, it is necessary to understand the significance of sports as cultural markers in late-nineteenth- and twentieth-century Ireland. Different sports belonged to different segments of society.

During the era of the Irish cultural Revival in the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, the “traditional” Gaelic sports of Gaelic football and, particularly, hurling were co-opted into a network of other cultural markers – such as the Irish language and its ancient legends, traditional music and even traditional dress – that defined a specific brand of Irish identity. The Irishness delineated by Revivalists was “native” and pure and separate and distinct from the culture of the English settlers who had colonised the island of Ireland several hundred years before and who had brutally suppressed and discriminated against the native population and its culture ever since.

So while Douglas Hyde’s Gaelic League busied themselves with their project of “de-Anglicising Ireland” through the means of reviving the Irish language that had been in severe decline since the time of the Famine, the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) pitted indigenous Gaelic sports against “foreign games” like soccer, rugby, hockey and cricket. The former were rooted in an authentic sense of Irishness, while those who play or watch the latter are regarded with suspicion as “West Britons” who are not really Irish at all. According to this way of thinking, rugby and, in particular, cricket were increasingly associated with Protestantism and Unionism – with an upper class and professional upper-middle class not really invested in a distinct Irish national identity – while Gaelic football and hurling were aligned with the nationalist ideology.

(The arbitrary nature of these division is illustrated by the fate of cricket in Ireland. That sport had been the most popular and widely played in Ireland up to the end of the nineteenth century. Even Michael Cusack, the founder of the GAA, had been a keen cricketer in his youth, and proposed to include it under the regulatory auspices of the GAA. Even after only narrowly missing out on being included in Ireland’s officially sanctioned sports, no sport became as synonymous in the Irish imagination with Englishness and as cricket.)

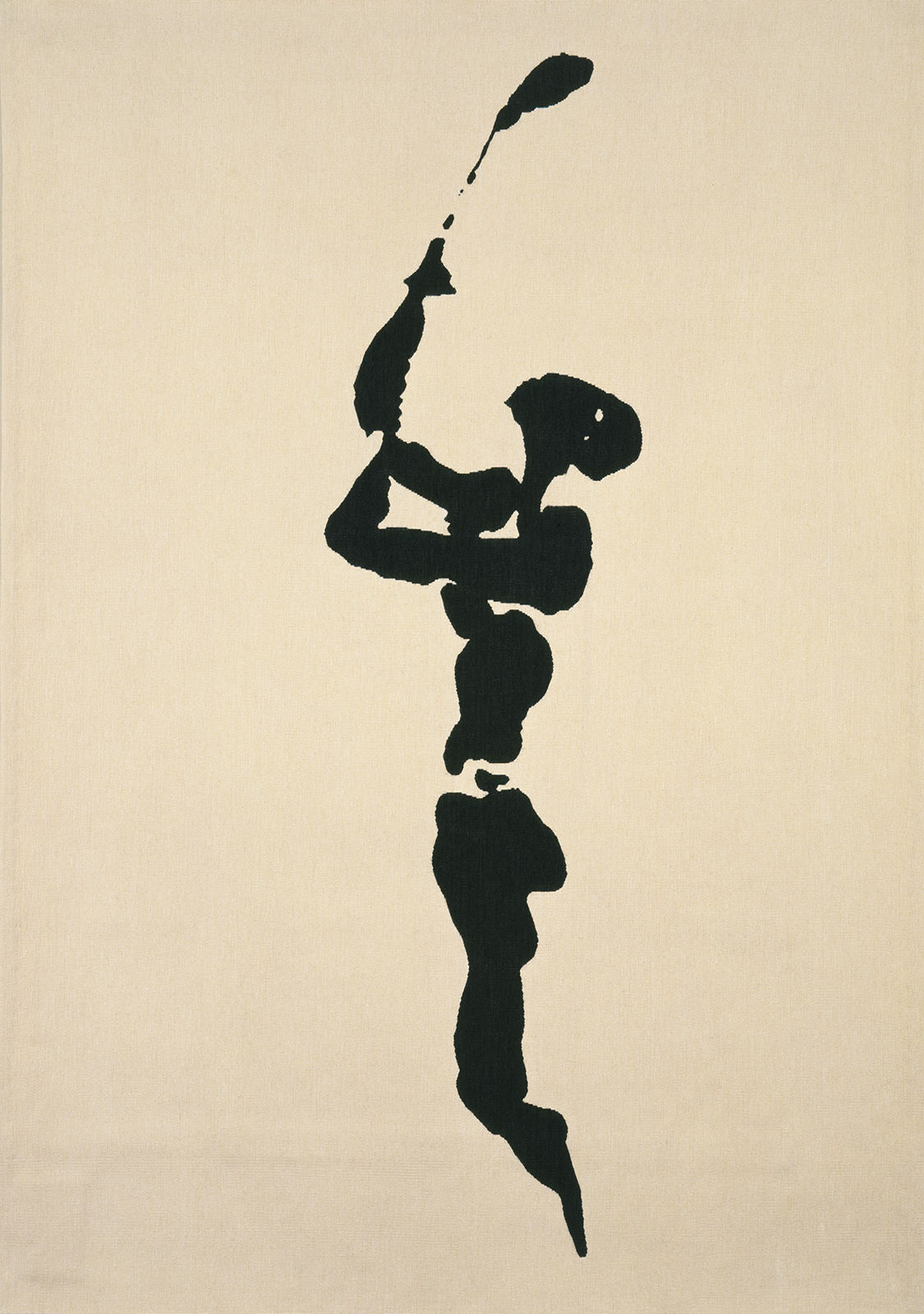

The popular narrative about the history of Ireland’s Gaelic sports is that they long pre-date the English colonisation of Ireland – and that they had been outlawed by the English ruling elite under the Penal Laws which sought to restrict the rights of Irish Catholics from the seventeenth to the middle of the nineteenth century. The evidence most commonly cited for the claim that hurling is the oldest stick-and-ball game in the world is that there is a reference in one of the ancient legends originating in the Iron Age. In the Táin Bó Cúailnge, such conventional wisdom has it, the legendary warrior Cuchulainn plays a game of hurling on the plains of Emain Macha – the royal seat of the king of Ulster – before a battle.

Placing the national sport in such an ancient context, lending validity to both the sport and the culture that invented it, made a lot of sense in the context of the nationalist rhetoric of the Revivalist period of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, when there was a need to construct a strong, distinct national identity which was grounded in the ancient Gaelic past. Asserting the vibrancy of an ancient pre-colonial culture validated the legitimacy of the contemporary claim for the cultural distinctness of the “native” Irish from the English neighbours who had invaded their country and imposed their own language and customs to displace those of the original inhabitants.

And the same argument continues to make sense in the context of the tourist industry, which thrives on selling the same romanticised narrative of Ireland’s unique cultural identity, and its heroic struggle against a larger foe, to tourists from Europe and North America … Indeed, this is more or less the version of the story of Gaelic sports that was presented to our students by the instructors of Experience Gaelic Games last week.

But while that conventional narrative about Ireland’s ancient sports may have served a useful purpose during the revolutionary period of the Irish Revival – and perhaps continues to do so still in a different context for the tourist industry – it is important to acknowledge a different way of thinking about its history too. That alternative way of thinking acknowledges the similarities between hurling and Gaelic football and its global counterparts rather than merely emphasise its separateness.

It is perhaps inevitable for a colonised nation to stake a rhetorical claim of ownership over their national sport – especially if that sport, or one very similar to it, is also played by the coloniser. But there is more than one way in which the empire can write back (to borrow the title of Bill Ashcroft, Gareth Griffith and Helen Tiffin’s book about post-colonial cultures). When the Indian public intellectual Ashis Nandy argued that cricket was an Indian game that was accidentally invented by the British, he was slyly repositioning the relationship between the colonial subject and the game their English overlords had imposed on them during the time of the British Raj. The Irish, in their own attempt to assert the primacy of their national sport in the face of British attempts to erase indigenous Irish culture and replace it with their own, decided instead to emphasise that their version was the original, while all British field sports were merely pale imitations of something the Irish did long before the first English public-school boy first picked up a pigskin and ran with it.

Age is key to this line of argument. Irish cultural nationalists have traditionally been keen to stress that their sports are older than the “foreign games” played by the English. (It has always struck me that for a nation that prides itself on not having a class system, the Irish as a nation display the classic signs of the aristocrat looking down on the nouveau riche (the “new money”) of the English, who may be materially wealthy but who lack the manners and good breeding of a truly ancient civilisation!) In this narrative, hurling – the game practiced by Cuchulainn in the Táin – is older than hockey, and Gaelic football older than soccer or rugby.

The truth is, however, that neither the Irish nor the English sport existed in their modern, standardised forms until the second half of the nineteenth century. One of the things that makes the history of the GAA so interesting is not just its fostering of a unique sense of Irish identity in the crucible of Revivalist Ireland in the 1880s and 1890s, but also – perhaps paradoxically – its position in the context of the emergence of other sporting governing bodies and codes during the same period.

Up to the first half of the nineteenth century, there was no standardised set of rules governing ball sports. There was no such thing as Association football (soccer) or rugby (either Union or League) or American or Australian rules football; there were just people playing with a ball, following whatever set of rules they had settled on locally. (So when Shakespeare refers to a “base football player” he is referring to the general roughness of all players of ball-sports, rather than contrasting the working-class fans of soccer with aristocratic rugby fans, as some modern readers might assume.) The need to standardise a set of rules only began to take hold from the mid-nineteenth century – and may be understood as an extension of western culture’s wider need for classification and codification in the wake of the Enlightenment that was also at the heart of a scientific revolution.

This happened over the course of a number of decades during the Victorian era. The first written rules of rugby date back to Rugby public school in 1845, while the English Football Association which codified the game of soccer was formed in 1863. Further afield, the laws of Australian Rules football were first published by the Melbourne Football Club in 1859, while in the United States the first intercollegiate American football rules were drawn up in 1873. Rugby League separated from Rugby Union in 1895 with its own distinct rules.

Similar things were happening for the codification of bat-and-ball games. Hurling shares DNA with such sports as hockey, lacrosse and shinty (a variety played in Scotland), as well as with cricket. Versions of a bat-and-ball game resembling any of these had been played by many cultures since ancient times (as borne out by literary and visual sources), but the rules of modern Lacrosse were only codified in Canada by William George Beers in the 1860s, while the rules that form the basis for the modern Olympic sport of field hockey were only written down by the Hockey Association in London in 1886. (The rules for cricket are the notable exception to this broadly common time-frame. They were first written down a hundred years earlier, in 1744 – although an oral tradition for those same rules can be traced back to at least the middle of the sixteenth century.)

Far from being a unique case, the establishment of the Gaelic Athletic Association at Hayes Hotel in Thurles in 1884 must be seen as a version of that wider trend for classifying and codifying a pastime that had had no standard set of rules before. The Irish, far from being ancient and archaic – as their claims for the venerable age of their games would suggest – were actually taking part in a very modern exercise when they codified the rules for their own version of football that was distinct from all the other rival versions while being similar enough to lay claim to the generic name of “football”. In writing down the codes and regulations of their sport and its governing body, the founding members of the GAA were taking part in a modern Victorian obsession with classifying and codifying every aspect of life that aligned them with their English, their American and their Australian contemporaries. In typical Irish fashion, though, the Irish were merely dressing up their extreme modernity in archaic traditional costume.

*

Another part of the conventional nationalist narrative about ancient Gaelic sports still niggles at me. What about the much-touted claim that hurling is the oldest bat-and-ball game in the world, one that – based on the evidence of the Táin – has been continuously played in Ireland since at least the Iron Age?

Many of those who repeat the claim that Cuchulainn was a hurler with the greatest certainty have probably not read the text on which that claim is based. It is true that the standard English translation of the Táin, by Thomas Kinsella, does indeed use the words “hurling-ball” and “hurling-stick”. But the section detailing Cuchulainn’s Boyhood Deeds does not elaborate on the rules of the game in which he and the other youths of Ulster compete; nor does it describe what a passage of play looked like. I have always been struck by the fact that the text repeatedly emphasises not the fast open play for which hurling is renowned, but rather Cuchulainn’s defensive capabilities. In one passage, he stops every ball the other boys fling at him, and a few pages later we are told that:

When it was their turn to shoot at the hole, all together, he turned them aside single-handed and not one ball got in.

Perhaps Cuchulainn was a goal keeper. But with its exclusive emphasis on the solitary individual protecting a target, and no mention at all of the shoulder-to-shoulder contest of open play in a sport like hurling or field hockey, it has always struck me that Cuchulainn’s defensive efforts more than anything resemble those of a cricket batsman at the crease protecting his wicket from being tumbled by attacking bowlers.

To put it bluntly: it is very possible that Cuchulainn was a cricketer.

Which brings us back to our momentous day last week, when Arcadia summer students were taught how to play hurling and Gaelic football on the cricket pitch of Trinity College. Perhaps the act of reverse cultural colonisation that appeared to be at work there – when the most popular sport of the subjugated, submerged population groups made its way into a site synonymous with the cultural practices of their colonisers – was not the full story after all. Perhaps the incursion of hurlers onto the cricket pitch was a homecoming rather than a hostile takeover – an act of reconciliation between two sporting codes ultimately derived from the same common stick-and-ball root. Or perhaps it was a form of unwitting pilgrimage, a visit by proponents of the modern Gaelic sporting code to the home of a sport that while it may be associated with Empire is probably much closer than they imagine to the one their Gaelic ancestors played in the time of Cuchulainn.

We cannot know what the game played by Cuchulainn’s contemporaries, or those of the tenth-century scribes who finally committed the ancient stories to manuscript, actually looked like, what its rules were. But it is fairly certain that it did not look exactly like either modern hurling or like cricket. What we can be certain of it that both those modern offshoots share that common ancient root, and it was heartening to see the old divisions in Irish society have broken down enough to welcome hurlers on the cricket pitch.